#L'atmosphère : Météorologie populaire

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The stars so sorrowful and falling, […] A night like this deserves the pen of Flammarion.

— Jonas Aistis, Perfection of Exile: Fourteen Contemporary Lithuanian Writers, (1970)

#Lithuanian#Jonas Aistis#Perfection of Exile: Fourteen Contemporary Lithuanian Writers#(1970)#Camille Flammarion#L'atmosphère : Météorologie populaire#♥

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shoot for The Moon 🌙

Inspired by the Japanese and Mayan moon rabbit folklore, and the 1888 Flammarion engraving from the book L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire.

instagram | prints & merch

#occult#illstration#digital art#surreal#astrology#occult art#creepy cute#weirdcore#moon#mythology#lunar#horror art#cw: gore#moon rabbit#moon hare#ooh look french so fancy ooh la la

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

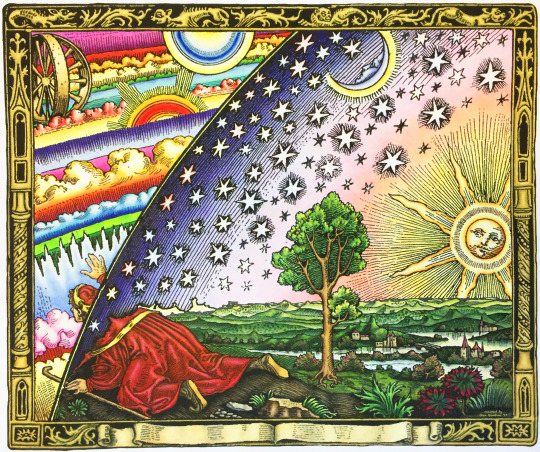

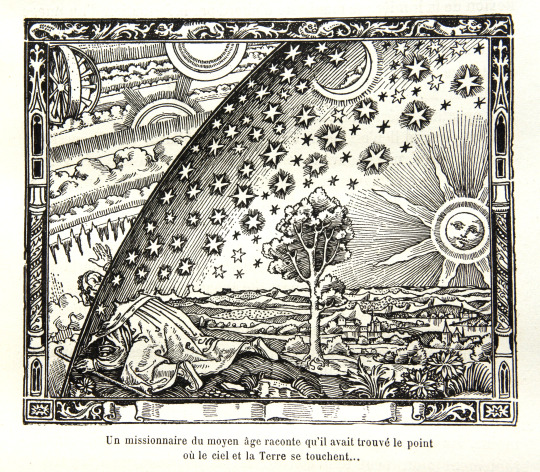

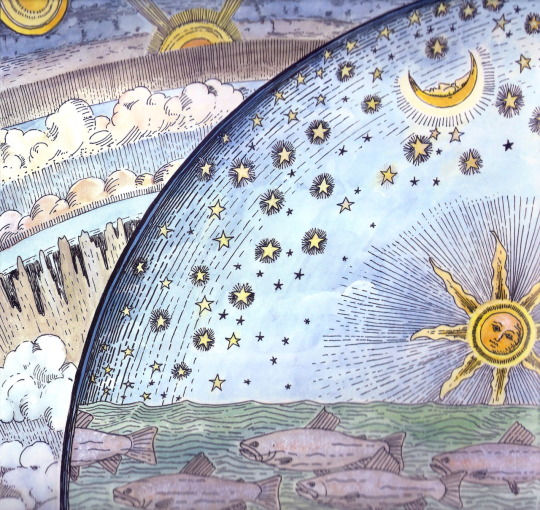

L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire, Camille Flammarion, 1888

“Flammarion engraving”

(p. 163)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist, so named because its first documented appearance is in Camille Flammarion's 1888 book L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology").[1] The wood engraving has often, but erroneously, been referred to as a woodcut. It has been used as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge and, more recently, of the psychedelic experience.[2]"

wikipedia

626 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist that first appeared in Camille Flammarion's L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire, 1888 book L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology"). The engraving has often, but erroneously, been referred to as a woodcut. It has been used as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge

The print depicts a man, clothed in a long robe and carrying a staff, who is at the edge of the Earth, where it meets the sky. He kneels down and passes his head, shoulders, and right arm through the star-studded sky, discovering a marvelous realm of circling clouds, fires and suns beyond the heavens. One of the elements of the cosmic machinery bears a strong resemblance to traditional pictorial representations of the "wheel in the middle of a wheel" described in the visions of the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel. The caption that accompanies the engraving in Flammarion's book reads:

A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he had found the point where the sky and the Earth touch

From Wikipedia: “In Flammarion's L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire, the image refers to the text on the facing page (p. 162), which also clarifies the author's intent in using it as an illustration:

Whether the sky be clear or cloudy, it always seems to us to have the shape of an elliptic arch; far from having the form of a circular arch, it always seems flattened and depressed above our heads, and gradually to become farther removed toward the horizon. Our ancestors imagined that this blue vault was really what the eye would lead them to believe it to be; but, as Voltaire remarks, this is about as reasonable as if a silk-worm took his web for the limits of the universe. The Greek astronomers represented it as formed of a solid crystal substance; and so recently as Copernicus, a large number of astronomers thought it was as solid as plate-glass. The Latin poets placed the divinities of Olympus and the stately mythological court upon this vault, above the planets and the fixed stars. Previous to the knowledge that the earth was moving in space, and that space is everywhere, theologians had installed the Trinity in the empyrean, the glorified body of Jesus, that of the Virgin Mary, the angelic hierarchy, the saints, and all the heavenly host.... A naïve missionary of the Middle Ages even tells us that, in one of his voyages in search of the terrestrial paradise, he reached the horizon where the earth and the heavens met, and that he discovered a certain point where they were not joined together, and where, by stooping his shoulders, he passed under the roof of the heavens.”

#Flammarion Engraving#L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire#Camille Flammarion#Wood Engraving#Art#Cosmos

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

from L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire by Camille Flammarion

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flache Erde/Flat Earth The Flammarion Engraving 1888 The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist that first appeared in Camille Flammarion's L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire (1888). The image depicts a man crawling under the edge of the sky, depicted as if it were a solid hemisphere, to look at the mysterious Empyrean beyond. The caption underneath the engraving (not shown here) translates to "A medieval missionary tells that he has found the point where heaven and Earth meet..."

291 notes

·

View notes

Photo

our cosmos explained -hehe-

Andreas Cellarius: Harmonia Macrocosmica, 1660-61. Chart showing zodiac signs and the solar system with Earth at centre. Plate 2: SCENOGRAPHIA SYSTEMATIS MVNDANI PTOLEMAICI (Scenography of the Ptolemaic cosmography). [img edited]

Helical orbits Solar system (imgur meme): Not entirely correct, scientifically (but cool) - Universetoday

Copernican system, post by: chainedtomysins & perrfectly & s-t-y-l-e-t-s

Geocentric model (Ptolemaic system), wiki [img source]

Unknown: The Flammarion (wood) engraving first appeared in Camille Flammarion's L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire, 1888. The caption underneath (not shown here) translates to "A medieval missionary tells that he has found the point where heaven and Earth meet..." [the Firmament]

Ancient Greek, Roman, and medieval philosophers usually combined the geocentric model with a spherical Earth, in contrast to the older flat-Earth model implied in some mythologies. The ancient Jewish Babylonian uranography pictured a flat Earth with a dome-shaped, rigid canopy called the Firmament placed over it (רקיע- rāqîa').

However, the geocentric model was the predominant description of cosmos in Aristotle’s in Classical Greece. It’s also called Ptolemaic system because Alexandrian astronomer and mathematician Ptolemy, optimized its accuracy in his Almagest and Planetary Hypotheses, ca. 150 AD.

The Antikythera mechanism, compatible with the Ptolemaic system, could predict the movements of Moon and Sun through the zodiac, the eclipses, to model the irregular orbit of the Moon and possibly (now missing) 5 of the 7 classical planets.

The Geocentric/Ptolemaic system persisted, with minor adjustments, but from the late 16th century onward, it was gradually superseded by the Heliocentric model of Copernicus (1473-1543), Galileo (1564-1642), Kepler (1571-1630) and Isaac Newton (1642 - 1727).

The transition between theories and perceptions is ongoing...

In the 6th c. BC, Anaximander proposed a cosmology with Earth shaped like a section of a pillar (a cylinder), held aloft at the center of everything. The Sun, Moon, and planets were holes in invisible wheels surrounding Earth; through the holes, humans could see concealed fire.

About the same time, Pythagoras thought that the Earth was a sphere (in accordance with observations of eclipses), but not at the center; he believed that it was in motion around an unseen fire. Later these views were combined, so most educated Greeks from the 4th century BC on thought that the Earth was a sphere at the center of the universe.

Greek astronomer and mathematician Aristarchus of Samos (c. 310 – c. 230 BC) developed a heliocentric model placing all of the then-known planets in their correct order around the Sun.

Hipparchus was in the international news in 2005, when it was again proposed (as in 1898) that his data may have been preserved in the only surviving large ancient celestial globe carried by the Farnese Atlas.

Lucio Russo has said that Plutarch, in his work On the Face in the Moon, was reporting some physical theories that we consider to be Newtonian and that these may have come originally from Hipparchus.

A line in Plutarch's Table Talk states that Hipparchus counted 103,049 compound propositions that can be formed from ten simple propositions. 103,049 is the tenth Schröder–Hipparchus number, which counts the number of ways of adding one or more pairs of parentheses around consecutive subsequences of two or more items in any sequence of ten symbols. This has led to speculation that Hipparchus knew about enumerative combinatorics, a field of mathematics that developed independently in modern mathematics.

source: wiki, Modern speculation

Britannica

#Earth#planet#cosmos#theory#philosophy#science#history#map#ancient#gr#Illustration#motion#model#mathematics#space#Flammarion#Andreas Cellarius#Ptolemaic#research

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

*imagem: Gravura de autor desconhecido, aparecida em 1888 na obra "L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire" de Camile Flammarion (1842 - 1925)

____________________________________________________________

T. S. Eliot – Quatro Quartetos (Excertos): Burnt Norton

O tempo presente e o tempo passado Estão ambos talvez presentes no tempo futuro E o tempo futuro contido no tempo passado. Se todo tempo é eternamente presente Todo tempo é irredimível. O que poderia ter sido é uma abstração Que permanece, perpétua possibilidade, Num mundo apenas de especulação. O que poderia ter sido e o que foi Convergem para um só fim, que �� sempre presente. Ecoam passos na memória Ao longo das galerias que não percorremos Em direção à porta que jamais abrimos Para o roseiral. Assim ecoam minhas palavras Em tua lembrança. ____________________________________________________________

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/oct/31/sofia-gubaidulina-unchained-melodies

Sofia Gubaidulina - Hommage à TS Eliot (1987) para octeto e soprano

https://open.spotify.com/album/2YOOENjLoeqJ1h9WphcwTa?si=ci7fnNenSyWVRbeARJmugA

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“If you feel like you don't fit into the world you inherited it is because you were born to help create a new one.” The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist, so named because its first documented appearance is in Camille Flammarion's 1888 book L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology"). The engraving has often, but erroneously, been referred to as a woodcut. It has been used as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge. A traveller puts his head under the edge of the firmament in the original printing of the Flammarion engraving. The print depicts a man, clothed in a long robe and carrying a staff, who is at the edge of the Earth, where it meets the sky. He kneels down and passes his head, shoulders, and right arm through the star-studded sky, discovering a marvellous realm of circling clouds, fires and suns beyond the heavens. One of the elements of the cosmic machinery bears a strong resemblance to traditional pictorial representations of the "wheel in the middle of a wheel" described in the visions of the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel. The caption that accompanies the engraving in Flammarion's book reads: “A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he had found the point where the sky and the Earth touch...”

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘‘ The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist, so named because its first documented appearance is in Camille Flammarion's 1888 book L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology").The engraving has often, but erroneously, been referred to as a woodcut. It has been used as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge.’‘

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flammarion_engraving

#The Flammarion engraving#quest#knowledge#camille flammarion#Flammarion#astronomy#hoax#fake#forgery#art forgery

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A traveller puts his head under the edge of the firmament

The image depicts a man crawling under the edge of the sky, depicted as if it were a solid hemisphere, to look at the mysterious Empyrean beyond. The caption underneath the engraving (not shown here) translates to "A medieval missionary tells that he has found the point where Heaven and Earth meet..."

The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist, so named because its first documented appearance is in Camille Flammarion's 1888 book L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology"). It has been used as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge.

The print depicts a man, clothed in a long robe and carrying a staff, who is at the edge of the Earth, where it meets the sky. He kneels down and passes his head, shoulders, and right arm through the star-studded sky, discovering a marvellous realm of circling clouds, fires and suns beyond the heavens. One of the elements of the cosmic machinery bears a strong resemblance to traditional pictorial representations of the "wheel in the middle of a wheel" described in the visions of the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel. The caption that accompanies the engraving in Flammarion's book reads: A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he had found the point where the Sky and the Earth touch...

In Flammarion's L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire, the image refers to the text on the facing page (p. 162), which also clarifies the author's intent in using it as an illustration:

Whether the sky be clear or cloudy, it always seems to us to have the shape of an elliptic arch; far from having the form of a circular arch, it always seems flattened and depressed above our heads, and gradually to become farther removed toward the horizon. Our ancestors imagined that this blue vault was really what the eye would lead them to believe it to be; but, as Voltaire remarks, this is about as reasonable as if a silk-worm took his web for the limits of the universe. The Greek astronomers represented it as formed of a solid crystal substance; and so recently as Copernicus, a large number of astronomers thought it was as solid as plate-glass. The Latin poets placed the divinities of Olympus and the stately mythological court upon this vault, above the planets and the fixed stars. Previous to the knowledge that the earth was moving in space, and that space is everywhere, theologians had installed the Trinity in the empyrean, the glorified body of Jesus, that of the Virgin Mary, the angelic hierarchy, the saints, and all the heavenly host.... A naïve missionary of the Middle Ages even tells us that, in one of his voyages in search of the terrestrial paradise, he reached the horizon where the earth and the heavens met, and that he discovered a certain point where they were not joined together, and where, by stooping his shoulders, he passed under the roof of the heavens...

#flammarion#engraving#empyrean#celestial spheres#art#medieval#middle ages#europe#european#alchemy#cosmos#celestial#cosmology#earth#sky#heaven#firmament#camille flammarion#astronomy#astrology#stars#traveller#pilgrim#history#cosmic#space#sun#planets#terrestrial paradise#mysticism

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Where heaven and earth meet... Originally from L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire by C. Flammarion.

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist, so named because its first documented appearance is in Camille Flammarion's 1888 book L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology").

It illustrates a person with a walking stick peeking through a veil of stars (firmament) into other worlds.

It has been used as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist, so named because its first documented appearance is in Camille Flammarion's 1888 book L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology"). The engraving has often, but erroneously, been referred to as a woodcut. It has been used to represent a supposedly medieval cosmology, including a flat earth bounded by a solid and opaque sky, or firmament, and also as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge.

The Flammarion engraving also appeared in Carl Jung's Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies (1959).

5 notes

·

View notes